How to Herniate a Disc

In a multimillion biomechanics lab at the University of Waterloo, the world’s leading expert on the spine has spent thousands of hours studying disc herniations. One of the most effective techniques he has discovered for herniating a disc is: crunches!

In fact, repeatedly rounding the back in a crunch or sit-up motion has been shown to induce over 3000 N of shear force on the discs of the spine (1-4). For some individuals, this has the potential to contribute to disc pathology.

Do crunches work the abs?

It is not very surprising that crunches can be harmful to the back. Most people know that squatting with the back rounded over is harmful, so it’s not surprising that an exercise that repeatedly puts us into this position could be unfavorable in some people.

Despite the potential negative effects on the spine, many people feel compelled to continue with these exercises in hopes that it will develop their abdominal muscles. Ironically, the benefits of crunches or sit-ups for abdominal development appear to be relatively unimpressive.

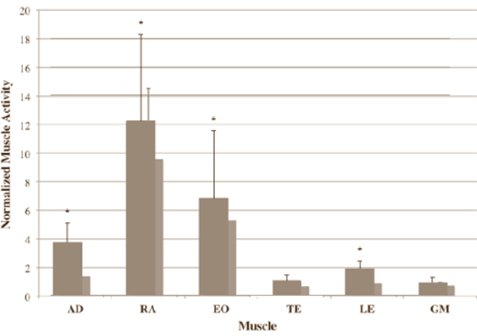

The following graph was taking from a study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (5):

The bar with the heading “RA” – rectus abdominus – represents abdominal activation. Researchers placed electrodes on subjects’ core muscles and measured EMG activity during various core exercises. The dark bar in the front represents the plank, while the smaller gray bar in the back represents the crunch. As seen in the graph, in all of the muscles surrounding the core, activation was higher in a simple plank compared to a crunch.

So, if crunches can sometimes be harmful to the spine and are relatively ineffective for ab training, what are the alternatives?

Effective Methods for Developing the Core

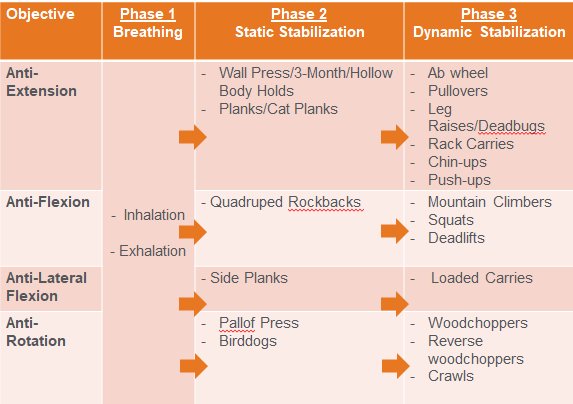

In order to begin developing the core, it is important to understand the core’s primary function. Although the core plays multiple roles, the most essential function is breathing.

Phase 1 – Breathing

During inhalation, the diaphragm is supposed to concentrically contract. During exhalation, the abs and obliques are supposed to concentrically contract to “internally rotate” the ribcage so that it moves posteriorly towards one’s back. This explains why balloon blowing has become prevalent in strength training facilities and physical therapy clinics, and why tennis players grunt so loudly before hitting the ball. Exhaling turns on the abs.

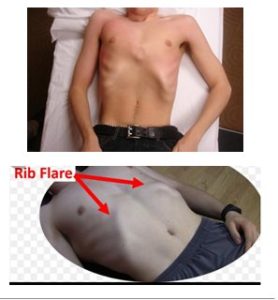

When the abs and obliques are not engaging during exhalation, the ribs become “stuck” in external rotation, which leads to a phenomenon often referred to as “rib flare”.

A simple test to determine if the core is engaging properly during exhalation is to lay down on the back and pay attention to rib position. If the ribs are sticking out at all (such as the individuals in the picture above), or the low back is excessively curved and not in contact with the ground, this is an indicator that you likely do not engage the core during exhalation. If the ribs are fully down and the low back is in contact with the ground, that is a good sign that breathing may be functional.

When the ribs are flared, the abs are chronically in a lengthened, inhibited positioned. Doing core training in this position will make it impossible to fully stimulate the ab muscles. Learning to exhale properly will place the ribs in an optimal position and will allow the abdominals to fully contract. Not surprisingly, studies have found that breath training leads to improved core activation (6). Along with improving the core, better breathing has numerous additional benefits.

Learning to breathe properly isn’t simply one component of core training; in reality, it is a prerequisite to all other core training. Once proper breathing mechanics have been established, it is possible to begin implementing the next phase of core training.

Phase 2 – Static Stabilization

What exactly does the term “stabilization” mean?

Core stabilization means to resist movement at the core.

Consider a crunch vs a plank: in a crunch, you are actively trying to create movement at the core. A crunch is the exact opposite of core stability.

In a plank, you are using your core muscles to resist movement, which makes planks a core stability exercise.

There are four directions that a strong core needs to be able to stabilize in:

Anti-Extension

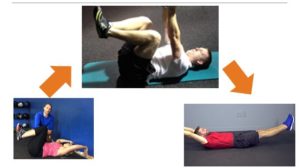

Extension means to be “arching” the low back. In general, it is typically advisable to avoid large quantities of exercises that put is into an extended position, such as this:

Instead, exercises that resist extension tend to be more favorable. The classic anti-extension exercise that everybody thinks of when it comes to core stability is the plank.

In theory, planks can be a good exercise if done with proper form. Personally, however, the plank is not one of my favorite core exercises for a few reasons.

For one, most people tend to perform planks similar to the top man in the image above. This man may think he is working his abs, but in reality, a lot of the tension is coming from his low back.

One alternative that I prefer is to do planks in more of a “cat” position (technically referred to as “All Four Modified Belly Lift) as seen below:

In the cat position, the low back muscles are being lengthened. Unlike a traditional plank, where it is very easy to overuse the back muscles, the cat helps inhibit these spinal erectors and teaches people how to properly engage the core.

Another alternative to planks that I prefer is the 3-Month position:

These can be essentially thought of as a plank on one’s back. Unlike a plank, in which most people have no idea whether their technique is proper, the 3-Month provides immediate tactile feedback from the ground to determine whether the correct muscles are engaging. As individuals begin to fatigue, their low back will begin lifting off of the ground, and this way they can instantly feel when the abs are losing control and the wrong muscles are taking over. This instant feedback makes this a great choice for learning how to stabilize the abs.

With a 3-Month, once the exercise becomes easier, we can make it harder by progressing to a Hollow hold.

On the other hand, if the traditional 3-Month is too challenging (for beginners, it usually is), then we can make it easier by placing the hands or feet on the wall for support. This way, there is a coherent progression system to keep pushing the abs to get stronger over the course of time:

Personally, this is my go-to for teaching beginners how to stabilize the core. There are four directions the core needs to stabilize in, however, so a well-rounded program will need to contain all four.

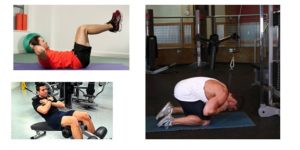

Anti-Flexion

The next direction the core needs to stabilize in is resisting flexion, which means rounding the back. In general, it is advisable to avoid exercises that actively put is into flexion such as these:

Instead, one of my favorite introductory exercises for anti-flexion is isometrically holding a quadruped rockback position using a swiss ball, as seen below:

As he drives his hips into the ball, the ball is pushing his low back into flexion, and his core must resist. If his back begins to round, the foam roll will fall off, which is providing him with instant tactile feedback whether he is completing this properly.

This exercise can be too easy for many people, but for people who struggle with resisting flexion, this exercise can be a good introduction to static stabilization.

Anti-Rotation

The third direction the core must stabilize in is to resist twisting. In general, it is advisable to avoid exercises that look like this:

Instead, my preferred exercise for anti-rotation is the pallof press, which is the polar opposite of a Russian twist. I initially teach people pallof press while on the back. As with the 3-Month exercises, the ground provides instant tactile feedback. If the back muscles are doing too much work, the low back will lose contact with the ground.

Once the exercise has been mastered in this position, we can make it harder by taking away support from the ground and progressing to a tall-kneeling pallof press. After this, there are harder versions such as half-kneeling or standing variations. As a result, we have a useful progression system as seen below:

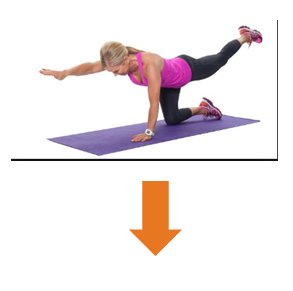

Other effective anti-rotation exercises that can be effective for training the core are isometric variations of the Bird Dog position:

Anti-Lateral Flexion

Another direction the core must stabilize in is to resist side-bending. For this reason, it would be best to avoid exercises such as this:

Instead, variations of the side plank tend to be extremely useful for lateral core development. I prefer to start with the knees bent and stacked on top of each other, and slowly progress towards lifting the legs apart and straightening the knees apart, as seen below:

Not only is this great for developing the core, but by integrating the external obliques with the contralateral glutes, this is highly functional and has a direct carryover to gait.

Phase 3: Dynamic Stabilization

All of the exercises mentioned so far have been static stabilization exercises, which means that they are entirely motionless. Static stabilization is great for making the core more toned and teaching beginners how to stabilize, but there are a few limitations.

Real life is not static. In the real world, the core does not act in isolation. During sports and everyday life, the core must work in synchronization with the rest of the body. This is what is meant by dynamic stabilization: the core is resisting movement while the hips and/or shoulders are simultaneously creating movement.

Once basic proficiency in the static stabilization exercises have been mastered, it is important to progressing to dynamic variations.

Anti-Extension

One way that the “Cat” exercise can be progressed to dynamic is by adding a wheel, which is essentially a moving plank:

View this post on Instagram

One way that we can progress a plank is to stand up to a rack carry or Zercher carry, which is essentially a moving plank.

One way we can progress a 3-Month is by moving to a deadbug:

Pay careful attention to the video – notice how she starts in rib flare with her low back arched and her abs inhibited. How does she fix this? She exhales. This woman has mastered phase 1 – breathing – and is using her exhale to turn her abs on. Once the abs are on, she is able to maintain that position, which is phase 2: static stability. Finally, while resisting movement at the core, she is creating movement at the hips and shoulders, which is phase 3: dynamic stability. This woman has successfully mastered all three phases of a proper core training program.

Think about the motion of this exercise for a second; while one arm is moving forwards, the opposite leg is doing the same. What does this motion resemble? This is essentially gait. Every time we walk or run, the arms and legs are moving reciprocally with one another. No matter what sports you play or hobbies you participate in, everybody needs to walk, and being able to properly stabilize the core during these motions is extremely valuable. I believe that this is something everybody should attempt to build up to in a core training program.

Anti-Flexion

A quadruped rockback can be made dynamic by standing up on the feet and performing a squat or deadlift. Most people believe that squats and deadlifts are the best leg exercises, but if you watch most people squat and deadlift, typical they will start out with good form but as the set goes on their low back will begin to round.

Why is this happening?

This often occurs because the core is beginning to fatigue, but the individual keeps pushing on in hopes of trying to fatigue the legs.

In reality, the core will often be the limiting factor in the squats and deadlifts. For this reason, I believe that squats and deadlifts are not the best exercises for fatiguing the legs, but they are incredible exercises for teaching the core to synchronize with the legs.

In a squat or deadlift, the core is resisting movement while the hips, knees, and ankles are simultaneously creating movement. This has immense benefit for athletes and is also valuable for anybody who sits, stands, bends, or picks things up off the floor.

In fact, research has found that in a specific subset of low back pain patients, teaching proper deadlift technique can dramatically reduce back pain (7) by allowing these individuals to shift stress away from the low back on to the hips.

Along with squats and deadlifts, another fantastic anti-flexion exercise is mountain climbers, which is essentially a squat pattern on the hands and knees:

As seen in the video above, proper technique is absolute paramount with this exercise. Like squats and deadlifts, it is essential to maintain a straight back and avoid any rounding.

Anti-Rotation

The best way to progress the pallof progress is to begin chopping and lifting patterns. In a chop pattern, the resistance begins high and moves to low, as seen below:

Alternatively, it is equally important to train the lift pattern, which begins low and ends high, as seen below:

Bird dog variations can be progressed to crawling:

Anti-Lateral Flexion

As with the regular plank, side planks can be progressed by standing up and performing a suitcase carry:

Putting it Together

If you talk to some of the best fitness experts in the country and ask what their favorite core exercises are, they may all give you different exercises.

In reality, however, although different experts have different preferences towards which specific exercises they utilize, most experts are all using a similar template to the one above. Progressing from static to dynamic anti-extension, anti-flexion, anti-rotation, and anti-lateral flexion exercises is based on universal functions of the core that are grounded in human physiology. Although different experts may prefer different exercises, the principles will always remain the same.

Whether your goal is to make the abdominals appear more toned, improve sports performance, or prevent injury,all of these goals can depend on following a proper, well-rounded core training routine.

References

1 McGill, S. M. (1995). The mechanics of torso flexion: situps and standing dynamic flexion manoeuvres. Clinical Biomechanics, 10(4), 184-192.

2 Balkovec, C., & McGill, S. (2012). Extent of nucleus pulposus migration in the annulus of porcine intervertebral discs exposed to cyclic flexion only versus cyclic flexion and extension. Clinical Biomechanics, 27(8), 766-770.

3 Wade, K. R., Robertson, P. A., Thambyah, A., & Broom, N. D. (2014). How healthy discs herniate: a biomechanical and microstructural study investigating the combined effects of compression rate and flexion. Spine, 39(13), 1018-1028.

4 Callaghan, J. P., & McGill, S. M. (2001). Intervertebral disc herniation: studies on a porcine model exposed to highly repetitive flexion/extension motion with compressive force. Clinical Biomechanics, 16(1), 28-37.

5 Gottschall, J. S., Mills, J., & Hastings, B. (2013). Integration core exercises elicit greater muscle activation than isolation exercises. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 27(3), 590-596.

6 Kim, S. T., & Lee, J. H. (2017). The effects of Pilates breathing trainings on trunk muscle activation in healthy female subjects: a prospective study. Journal of physical therapy science, 29(2), 194-197.

7 Berglund, L., Aasa, B., Hellqvist, J., Michaelson, P., & Aasa, U. (2015). Which patients with low back pain benefit from deadlift training?. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29(7), 1803-1811.